The Night of the Black Chief

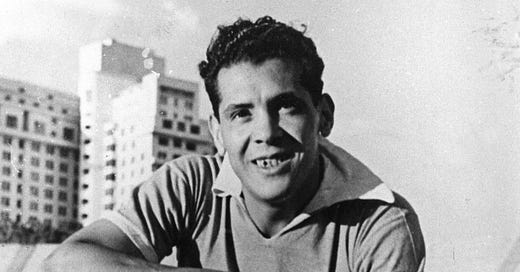

The greatest upset in World Cup history and the iconic Uruguayan captain who engineered it all.

Sometimes I think about the Maracanazo: that famous World Cup Final in 1950, nearly 72 years from this very day, when Uruguay, against all odds, defeated Brazil in Brazil—the first and only time, before or since, that a nation has defeated the hosts in the final of the world’s most important tournament.

That July 16, two-hundred thousand spectators—the most to attend any sporting event at any point in history—were packed into the Maracaná stadium like sardines. It had been 12 years since the last World Cup final had been played, the war that engulfed Europe and Asia peering out from a shallow grave.1

The Brazilian fans were delirious with anticipation. The morning of the final, the Rio newspaper O Mundo, had printed the headline, “Here are the World Champions!” The federation had already prepared 22 custom-inscribed gold watches for the team. FIFA’s French president Jules Rimet had been up all night, working meticulously on his speech, prepared in Portuguese, to give once the inevitable had taken place. He kept it tucked inside the right-hand pocket of his coat as he took his seat.

To everyone, outside of the 11 Uruguayans on the field, a coronation was 90 minutes in the making.

The World Cup in 1950 was not the business it is today. Only 16 nations qualified. There were two stages: an initial group stage, from which the four first-placed teams would then be placed into a second group stage. Each would then play each other once, and the team with the best record would claim the championship.

To earn its place in the final, Brazil had beaten Mexico 4-0, drawn Switzerland 2-2, and defeated Yugoslavia 2-0. In the second group, the Brazilians walloped Sweden 7-1 then let up on the gas against Spain, which they defeated 6-1. Theoretically, the hosts could’ve drawn Uruguay on the last match day and still been crowned world champions.

Uruguay’s lead-up couldn’t have been more different. Shortly before the World Cup was due to start, three of the qualified nations—Scotland, India, and Turkey—withdrew, meaning two of the initial groups, including Uruguay’s, were left uneven. The French FA initially accepted an offer to step in, but at the final moment the players elected not to board the ship. That left Uruguay with only lowly Bolivia to compete against in the first group stage. They won 8-0 and watched the other matches from their hotel rooms while playing cards.

If the Brazilians were on a high after scoring 13 goals over two matches, the Uruguayans were in desperate search of a spark. After tying Spain 2-2, they were 2-1 down to Sweden before goals in the 77th and 85th minute by Oscar Miguez ensured both teams would have something to play for in the tournament’s final game.

The Brazilians and Uruguayans were no strangers. Only two months prior, Brazil had defeated Uruguay in both legs of that year’s Copa Rio Branco, a competition the two nations played between each other for many years.2 The Brazilians had watched their tiny neighbors to the south claim the first World Cup in 1930 and felt it was their moment to step out into glory.

Few experts had even expected Uruguay to make the final; the squad had been carelessly assembled, leaving out several key players, days prior to the tournament, which Uruguay made by default after Argentina, Ecuador, and Peru refused to participate. In the locker room after their final training session, a dignitary from Uruguayan football came to meet with the players. “You men have already fulfilled your ambition—lose by less than four goals and walk away with your heads held high,” he told them. The next morning, another paper-pusher from the federation showed up with 20 copies of the newspaper that bore the headline already declaring the Brazilians champions.

Nono, my grandfather, used to tell me this story.

At roughly 2:45 p.m., 15 minutes before game time, the Uruguayans were gathered together one last time. The ceiling and walls of the Maracaná shaking from the weight of the supporters above, the men were about to be thrown to the lions.3 The head coach, Juan Lopez Fontana, told them to go out and defend for their lives. The animals would devour them regardless; their only objective was not to be eaten alive too quickly. After Fontana left the room, Obdulio Varela—El Negro Jefe (“The Black Chief”), the team’s captain and spiritual leader, rose to his feet. “Juancito is a gentle man and we adore him,” he said.

“But when we walk out onto the pitch, don’t look up at the stands. The game is played on the field. The ones in the stands are made of sticks. The game is won with the balls you carry on the end of your boots!”

I’m crying as I write this, because what happens next is unbelievable in any context outside of the one in which it took place. In the first half, the Brazilians did attack relentlessly, raining crosses and shots from every direction, pinning the Uruguayans back as Varela pressed his men forward to no effect. By some miracle, the score was even at halftime. But the proud Uruguayans were exhausted from holding their hands up to the tsunami that sought to engulf them.

In the 47th minute, Albino Cardoso Friaca opened the scoring for the Brazilians. The crowd erupted in a deafening roar. The dam was broken. And with it a torrent of other goals were expected to follow, just as they had every match before.

El Negro Jefe knew that as well as anyone.

A day before, the Uruguayan captain had taken the copies of the front page that declared Brazil champions before a ball was kicked and spread them out in the urinals, instructing his men to go and show the Brazilians what they thought of their impending doom.

While Friaca celebrated with his teammates in the corner, before anyone else could make a move, Varela rushed to grab the ball from the back of the net. He placed it firmly under his arm and ran to the English referee protesting. It was offsides, he shouted in Spanish. The bewildered English referee had no idea what The Black Chief was on about; just as Varela spoke no English, George Reader knew not a word of castellano. “Of course, there was no offsides,” Varela would say later. Tenía que enfriar el partido o nos comian vivos. If he didn’t do something, he knew his countryman would be eaten alive. At one point, Alcides Ghiggia approached Varela to collect the ball and restart the game, but the captain shouted at him: “We either kick up a fuss or they will kill us!”

The confusion had momentarily silenced the crowd and, with it, the Brazilian attack. Soon the Uruguayans were playing themselves back into the game.

In the 66th minute, Varela played a pass out to the right to the feet of the Ghiggia. The tricky winger, who died in 2015, the last player from that final to see the light of day, beat his marker then sent in a cross to Juan Alberto Schiaffino, who hit it one-time past Barbosa on his near post. The tide had turned.

Throughout the second half, Ghiggia used his speed and trickery to dance circles around the defense. At one point, Bigode tackled the winger hard, intending to deliver a message. But Varela raced in and, with the referee’s back turned, smacked the Brazilian defender hard around the ear, rattling him.

That message was well received. In 79th minute, Varela played Ghiggia in once more. The Uruguayan beat Bigode and hit it low and hard to the near post. The ball was in past Barbosa.

“The silence was morbid,” Rimet said after. The stadium had become a graveyard. One of the Brazilian players said the silence of those final minutes terrorized him. Until his death, he slept with the windows open and the radio on, fighting against the dead air that would trigger the nightmare from playing back over and over again in his mind.

Barbosa, one of the finest keepers of his generation, retired immediately after the match. Decades later, while working as the director of a public pool in the countryside, he was given a piece of one of the wooden goals from the Maracaná—that same night he used it to cook a barbecue with his friends. But even that did not exorcise his demons. “The sentence in Brazil for the worst crime you can commit is 30 years,” he said in an interview before his death in 2000. “But I’ve been condemned to suffer since 1950.”

Improbably, Uruguay were World Cup champions. In the chaos that followed the final whistle, there was no time for a ceremony; FIFA officials found Varela and handed him the trophy without any fanfare. Rimet tossed the pre-written speech in a garbage can beside the tunnel. It was the last time Uruguay would play a world final, the closing chapter on the greatest era in their football history.

“It was simply chance,” said Varela about that night. “We might have played them 99 more times, and we would have lost every match. That’s the thing with football. Sometimes the unexpected plays a role, things that are beyond all reason, beyond all logic.”

There are fantastical, true stories of what happened after the cameras cut off. What I remember most vividly is Nono telling me that immediately after the final whistle Brazilians flung themselves to their deaths from the tops of the stadium; and it appears true that some spectators did commit suicide: 70 were reported nationwide the night of the final.

The Uruguayan squad, swept up in the hysteria of their unlikely victory, were abandoned by their federation and given no money for food. So after departing for their hotel, they scrounged together what they had in their pockets for sandwiches and red wine. A week later, the Uruguayan FA announced it was rewarding each director with a gold medal for their efforts. Only after a public outcry were Varela and his teammates also recognized by their leaders; they were given silver medals and a meager bonus. Varela used his money to purchase a 1931 Ford, which was stolen a week later.4

The Black Chief, one of the most beloved deep-lying playmakers of his era, had been born poor in Montevideo, selling newspapers in the street until his footballing skills could earn him a paycheck, and died, in 1996, not much better off. He played in the times before players were millionaires—when some, like Garrincha, died penniless and drunk, and others did their best to squeeze out a modest living coaching youth teams or running cafes. You can see it in his clothes, in the setting of his final interview in the living room where he spoke not much differently than how my grandfather speaks to me when he tells me stories like Varela’s.

El Negro Jefe was a man of tremendous pride—not the inventor of the mythical garra charrua,5 the never-say-die spirit of the Uruguayan footballer, but perhaps its best embodiment. After signing with Arsenal in the English Premier League in 2018, Uruguayan midfielder Lucas Torreira6 was asked to explain the concept in an interview—a question that is the equivalent of asking why the sky is blue or blood red.

“It’s a way of living football that all Uruguayans grow up with,” he said. “It’s inside every Uruguayan. It’s the way we feel football, the way we feel the shirt, the effort we put into each game. It’s about the spirit that exists inside the national team.”

Five years before the Maracanazo, while Varela was playing for Peñarol, the club’s directors sought to reward him and his teammates for a victory over Argentine giants River Plate: for each player, 250 pesos, and for The Black Chief, as the captain, 500 pesos. He refused: “I didn’t play any more or less than anyone else,” he said. “If you think I'm worth a 500-peso bonus, then you give everyone 500 pesos. If they only deserve 250, then so do I." The frustrated management relented and gave everyone the heftier paycheck.

Perhaps the saddest story of the 1950 World Cup Final—the one that could not be turned into a feature film or an inspirational children’s story of David besting Goliath7—took place that night, once Varela’s teammates had gone to bed.

Seeking one last drink, The Black Chief ventured out into the streets of Rio, hoping no one would recognize him. As he did so, he came upon dozens of teary-eyed Brazilians, their heads fixed on the cement in front of them, lament written all over their faces. “I hated them, when they were that monster with 200,000 heads,” Varela told the journalist Eduardo Galeano decades later. “But when I saw them one by one, it broke my heart. I hugged them. We shared a beer, some shots. And they said, crying, ‘It was Obdulio! It was Obdulio.’ I didn’t tell them it was me. I was afraid they might throw me into the river. But the entire night I spent it like that, in the arms of the defeated.”8

The memory was so fresh that Germany and Japan, both still occupied by Allied powers, were not permitted by FIFA to participate. Behind the Iron Curtain, Czechoslovakia, which finished third place in 1934, Hungary (finalists in 1938), and the Soviet Union also refused to travel for the tournament.

Read a great story, in Spanish, about the Copa Río Branco and the rivalry between Brazil and Uruguay in those early years here.

This is a complete aside—but perhaps it comes in handy come trivia night. The idea of being thrown to the lions comes from the Roman form of capital punishment Damnatio ad bestias (“condemnation by beast”). A form of entertainment for the lower classes of Roman citizens between the first and third centuries AD, soldiers rounded up runaway slaves, Christians, and the worst criminals, and confined them in an arena, where they’d release lions, tigers, and bears (oh my), to feast—kind of like the Russian Demagorgan arena in Stranger Things 4. More info at this Wikipedia page.

Later in his life, Varela said that, if he had known before the match how he and his teammates would be treated by their federation, he would’ve turned around and kicked the ball into his own net as soon as the ref blew the first whistle.

This is no easy concept to translate to English. But These Football Times did a wonderful job of summarizing it in 2020:

“There are many explanations for its meaning but, at its core, Garra Charrúa – literally ‘Claw of the Charrúa’ – is about tenacity and courage in the face of adversity, about being resourceful and daring, to never give up. Long before Forlán, Luis Suárez and Enzo Francescoli, there were the native Charrúa, the indigenous people who inhabited the land before the conquistadors came calling. History recalls the stoic resistance they put up fighting to defend their territory against the Spanish invaders. It was a battle they could never win, of course, and would ultimately lead to their betrayal by the president, General Fructuoso Rivera, and their wholesale extermination in a final, brutal massacre in 1832. Their spirit lives on in the characteristics that Uruguayans have chosen to embrace and make their own; of fighting against the seemingly impossible, of believing that with grit and tenacity, anything is possible.”

Diego Simeone, the iconic Argentine manager who Torreira won the Spanish league title with in 2021, said years earlier, after his Atletico Madrid side bested Chelsea to make the UEFA Champions League Final, that he wanted to thank the mothers of his players, porque estos jugadores nacieron con unos huevos así de grandes. They were born with balls the size of watermelons. And there’s your analogy: to demonstrate garra charrua, you must play as if your balls are watermelon-sized.

I use this analogy here for ease of understanding, even though I explained in this story about St. Peter’s University’s unexpected run to the Elite Eight earlier this year that most people talking about David vs. Goliath stories seriously misunderstand the actual encounter between the shepherd boy and the warrior.

I pulled from. a lot of sources for this essay. If you want to learn more about the Maracanazo or The Black Chief, go to these articles from La Vanguardia (Spanish), These Football Times, and ESPN.