'Nobody Cares; Keep Running'

Recounting my first half-marathon and newfound pleasure in kissing feet to pavement.

In April, I ran my first half-marathon with a single goal in mind—to not, at any point or for any reason, stop running.

Each race weekend dating back to 2021, I’d watched many thousands of runners chasing the numbers 13.1 and 26.2 pass from the front lawn of a friend’s house in Sequoyah Hills. Each time, with a half-chewed bagel in my mouth, I told Haley, “Man, it would be so fun to do that.” Even though my thighs touch at the knee and I hadn’t run a mile since 2020.

So when my wife, who’d run last year’s edition seven months after having her belly sliced in half, asked me, in July, if she could sign us up, I responded, “LFG.”

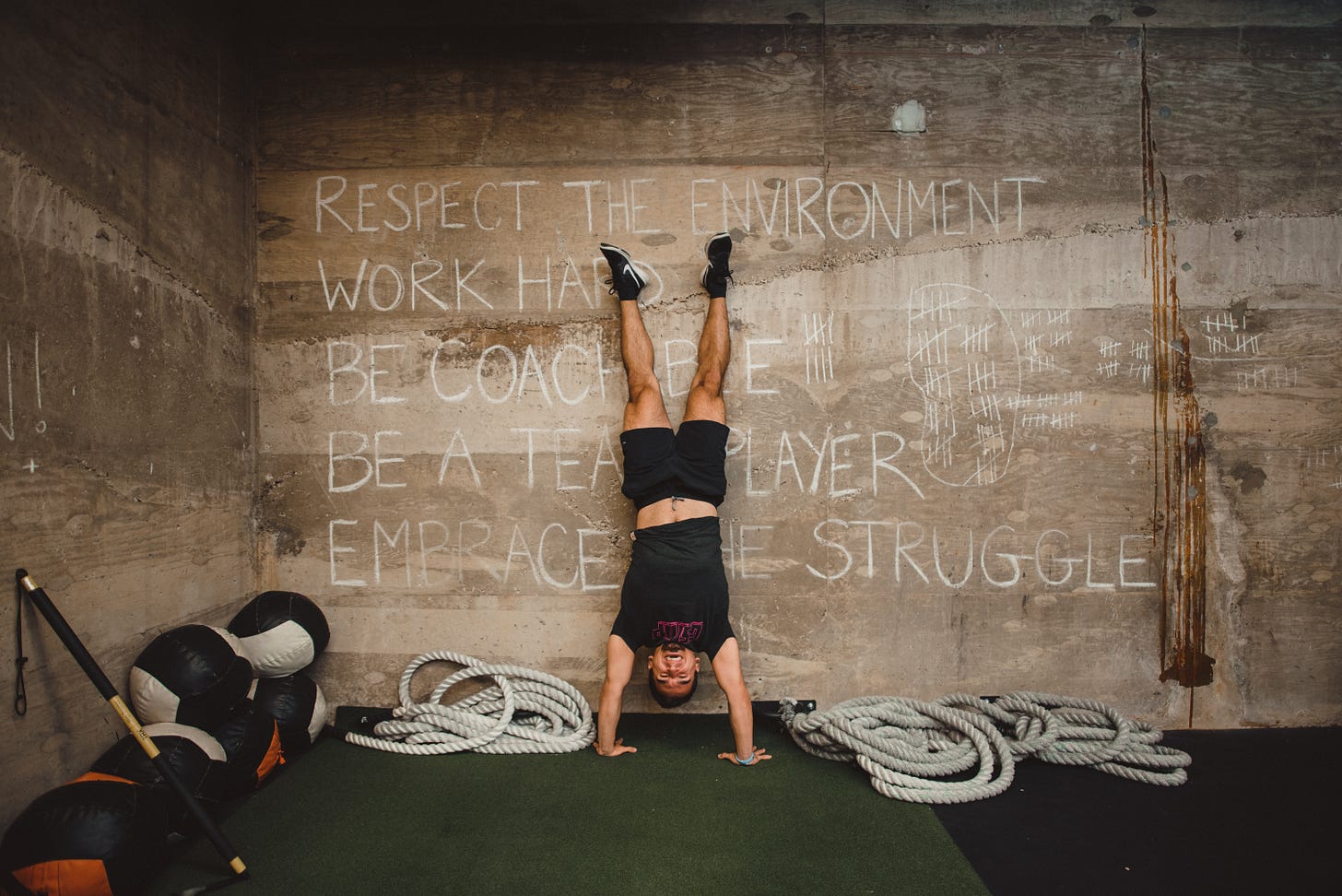

For most of my 30-something years, I’ve been a heavy-set dude. A body fueled by Diet Cokes, cold cuts, and Little Debbies. As such, not a single muscle was visible beneath my skin and blubber until the age of 26, when I started training at an MMA gym in South Knoxville to gain self-confidence. That first year of fitness, I went hard in the paint1, leading a full-on assault against my love handles and dropping so much weight that I paid an Italian tailor slim down all my dress clothes.

But as proud as I was of my belly meat no longer rubbing against my buckle, and that I could now swim with my shirt off, I discovered something even more seductive than being skinny: beating people.

They do not tell you this about fitness as a grown-up. The PR folks find workarounds, telling you it’s about healthy living, avoiding heart disease, chasing your grandchildren when you’re older. If you’re divorced, as I was, or single, closing in on the expiration of your procreation window, the more honest ones might whisper that being fit will help you attract hot chicks and dudes.

But the absolute best part of working out is crushing the person working out beside you. Sorry to say it so frankly. But Jesus wouldn’t have me lie to you.

In 2017, I transitioned from MMA to CrossFit. For one, because I realized, after getting my nose kicked to one side, and then, a minute later, the next, by a 16-year-old kickboxer, that I would have a better chance at winning a contest that did not involve fisticuffs against trained killers. (Meeting a woman with all her teeth who couldn’t choke me to death was a secondary motivation.)

In the box, I was no Hercules, but I set personal goals, broke them, then set bigger ones. I cried when I could finally squat 275 pounds. A year later, I squatted 400. I beat younger, fitter dudes in grueling workouts at local competitions because I committed myself to out-suffering anyone who I could match for skill. I yearned to be laid out in a sweat puddle on the black mats, hyperventilating, while other dudes circled me like crows, high-fiving and saying, “Brooooo, let’s gooooo,” as I tried not to die.

But then came the Dad years.

And for reasons every parent knows too well, I quit all the fun stuff in my life and got a family membership at the YMCA, where I work out at 6 a.m. with 70-year-old women and other parents looking to sweat before sitting at computer screens all day.

Running, I figured, was the least expensive, time-consuming way to beat someone at something again.

My first “training run” was the week before Thanksgiving. I went 3.4 miles at an 11:14 pace. And, as I trotted out onto Emory Road, I couldn’t even remember basic things, like whether you’re supposed to bend your knees, and if it’s supposed to sound like you have sleep apnea as you pound the pavement. My lungs burned, and my legs and back were sore. But I kept running through winter until I got up to five- and six-mile sessions, longer than I’d run since trying to impress a pretty girl on my soccer team I wanted to participate in the act of making children with.

At the Y, I began every workout with a few miles on the treadmill. The older ladies I’d befriended, who’d watched me tiptoe past the cardio machines for two years, were worried about me. “Did the doctor tell you you’ve got diabetes?” they asked. “No, ma’am,” I reassured them. “And my wife ain’t leaving either!”

The only illness that I bear is mental, my only departure from reality.

“Alright, honey,” they said. “Just be careful.”

Two weeks before the Knoxville Half, I ran my longest distance ever: 10 miles along the Third Creek Greenway. I felt awful and slow—no matter how much I run, the first two miles are always terrible—but I lumbered forward. The heavy metal in my headphones drowned out the sounds of my labored breathing. I texted Haley after finishing to ask if I could have a meat-lover’s pizza as a reward. (She said yes.)

The night before the half, my stomach churned for other reasons.

Part of it was anxiety about the forecast, which predicted rain and thunder, meaning either the race would be cancelled or that my sausage legs would go raw from chafing. But the rest was the fear of falling short of expectations.

In my training, I always ran alone. Being lapped by my wife, who is built like a greyhound and often pushing at least one toddler in a stroller, would’ve demoralized me. So when the storms relented and we made it to the starting line, I told her to proceed alone, find some other skinny people to chase. And I set my sights on other Clydesdales—fellas with thick trunks and bellies—who stared back, feigning smiles. We’d zeroed in on each other, like we once had years before at K-Mart when our mothers forced us back to find pants labeled with the dreaded “H,”2 knowing it was not the world that was our competition, but each other.

When I was a mediocre CrossFitter, the only workouts I had the slightest chance of winning were the slogs punctuated with bursts of cardio. I was a weak lifter with bad gymnastics. But even when my legs were putty, I would (and did) eat concrete to inch past the man beside me. So I applied the tactic to the race: if I could find a comfortable pace through the first 11 miles, then I’d sprint the last two. Even if I’d been passed by a thousand folks before, my mindset would remain unbroken if I could blow by at least a few of them at the end.

The plan worked. From the moment that I left Tyson Park, entering the Fort, I picked up the pace and wasn’t passed by a single soul—mostly, because all the fast people had already finished.

And I was surprised to find that every person I passed renewed my energy. The younger, fuller-haired, and more muscular, the more strength I gained as I hurdled toward the finish.

“It’s called paratrophic vampirism,” my friend, Wolfman, a veteran of more than 20 marathons, including Boston, NYC, and every one of Knoxville’s, told me a few days later over coffee. I went to him in an attempt to understand the feeling. And, as he was the one who’d recommended rubbing jelly on my privates and using band-aids to preserve my nips, I trusted him.

“It’s a callback to our animal instinct,” he said. “The lion feasts on the injured gazelle. A bat feasts on the blood of the man who lets himself be caught.”

When you encounter a slow or injured person, he explained, you must visualize yourself draining what remains of their precious life source. Making the actual sucking sound—sschluurrrp—as you sprint past allows for an even greater transfer of energy. “Forget the gels,” he said. “I haven’t needed a sip of water in years.”

In the end, I ran my first half in 2 hours and 19 minutes (a 10:35 pace), good enough for 1094th place.3 My last mile, at 9:17, was more than half a minute faster than my first. And now I have a clear goal ahead of my next race—because, of course, there will be a next one.

I never thought I would enjoy running.

For the years that Haley tried to get me to join her on a jog after my deception was complete and I started shedding workouts to make room for pounds, I made every kind of excuse—too old, too tired and stressed, and busy, my legs would chafe. Excuses come naturally when I seek to justify my inadequacies, failures, and regrets.

But halfway through the race, on Sequoyah Ave, as the rain poured down and the hills came into view, when you might want to quit swinging those arms, a yellow sign on a tree read, “Nobody cares. Keep running,” in big, bold font.

It’s a simple message, but one that I’ve taken to heart as I’ve added longer runs to my weekly routine, clocking more miles from Monday to Friday than I did during entire decades of my life. Right now, in fact, I am regretting not being outside with the Strava giving me my latest split.

What kind of topsy-turvy world is this?

Life will only get busier and more hectic. But I hope, if you’re strolling down the Halls, Sterchi, or Third Creek greenways in June, you’ll see me trudging along, huffing and puffing, but never quitting.

Before you leave, support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription for as little as $4.17/month ($50/year). You can also buy me a coffee, order a copy of either my first story collection or my epic Ping-Pong novella, or listen to my stories on YouTube and Spotify.

Waka.

Big boys, again, know this memory too well. Though I believe the softies running things today have switched the label to “extra wide,” we’ll always know it as husky.

Wolfman, by comparison, is a decade older and finished the full marathon, just over an hour later. You may know him if you see him, a skinny, gray mustache bobbing through graveyards of South Knoxville, a flash among the headstones.