'Brett Martin, You a Nice Man, Yes'

On teaching young people, creativity, and ways of getting noticed on the internet.

Hi readers. Today, Paddlehands: The Most Epic and Absurd Ping-Pong Story Ever Told, was released on Kindle. The audiobook will be available on Audible next week. Each is $5. If you’d like to purchase directly from me and receive a PDF, EPUB file, or MP3s, write me. Attic Club members will receive their complimentary copies soon. Thank you for your support.

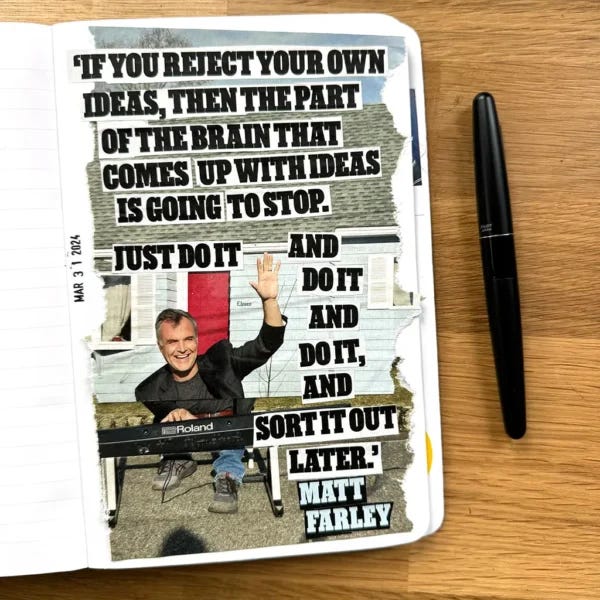

TL;DR 1: Read or listen to Brett Martin’s New York Times profile of oddball musician Matt Farley and watch his performance on World Café from April. Then, consider: what is the relationship between creativity and commerce? What constitutes art? What is really just spam?

TL;DR 2:

Things I love about Matt Farley

He is an unabashed user of Wikipedia.

He doesn’t curse in any of his 25,000 songs available on Spotify, even the ones about poop.

He reminds me of who I was at 17, when Mickey, Jeremy, and I decided our sole mission in life was to defeat Eddy Fink and become Bayonne Ping-Pong champions.

He’s a dad who’s figured out a way to do something he enjoys while hanging out with family and making people smile instead of doing spreadsheets and being grumpy that his day job keeps him from fulfilling his life’s purpose.

He made Raina Douris, the host of World Café who invited him on her show in April, say, “That was one of the best and strangest moments of my broadcasting career so far,” when he and his dad friends performed, “People Like Raina Douris (Because She’s) Great” from his album I Feel Dumb Singing About Famous People So Much But It’s All I Know.

He’s proof there is still a way to be happy in a world where everything seems to be burning, depending on who you listen to or how much time you spend on Facebook.

This semester, I taught two classes at the university. The first, media writing, was an online course populated with mostly first- and second-year students taking it only because it’s required. The second, feature writing, is my favorite of the many courses I’ve taught in eight years as a professor, for two reasons: one, it’s an elective taken mostly by seniors who love writing, and two, nobody else teaches it, meaning I can shape the course to be my own. (MWAHAHA.)

My approach to teaching is less instructor and more curator, facilitator, and coach. I accept that most of my students don’t read—they admit this to me in an anonymous survey I send out at the start of the semester—and will use ChatGPT for their easiest assignments, even when I do a live demonstration of how I will catch them. Since university administrators—everywhere, not just here—put computers in classrooms and don’t have policies preventing students from playing on their devices in class, pretending they’re taking notes while really on iMessage, I accept that even I, a cool and understanding younger professor, will be mostly ignored.

So instead of wasting my time building PowerPoints, I find the best journalism online and make them read it. I come up with activities that force them to get off their devices. I try to engender creativity because I believe that’s our only hope against the impending robot invasion.

On my reading list for my courses are stories about a wanderlusty college senior who puts off a career to move to the last remaining leper colony in Hawaii (“When We Are Called to Part”); a pair of amateur pet detectives in South London who set out to discover who’s killing their felines (“Cat and Mouse”); the death of two young men, one by the falling towers on 9/11 (“What Bobby McIlvaine Left Behind”), the other murdered while jogging in Georgia (“Twelve Minutes and a Life”).

I mix in the serious, social and politically relevant—for example, “Adrift,” about a boat containing the rotted corpses of West African men that washes up an ocean away, a story not of murder but of the casualties of poverty and the refugee crisis—with the goofy, like “My Dad Tried to Kill Me with an Alligator Once,” by Harrison Scott Key.

Two weeks ago, with the semester coming to a close, I realized that few of my students would remember anything I taught them. But like any older person in the presence of those who remind them of who they were once, I felt the pressing need to leave them with something important to consider as they go out into the world.

So, I spoke about Matt Farley.

I realize this was a very long introduction to talk to you about this weirdo from Connecticut who’s figured out a way to make a living writing songs about poop. But hang on for a second, and I’ll explain why.

In an age when nearly all professional work relies on an array of different computer software for project and client management, media and design production, AI—the thing that will replace us—has become a valuable and necessary tool. Much of what white-collar workers do is monotonous and boring, relying on creativity only for figuring out how, like my students, to get out of doing what we really don’t want to do.

This isn’t just true today—watch Office Space, the cult classic from 1999. The problem plagued us well before smartphones and the Cloud. It doesn’t help that, in journalism, any job that pays a living wage is going to demand mastering your “online brand” and engaging with audiences non-stop via social media rather than spending weeks chain-smoking alone at your desk trying to come up with a narrative for a 5,000-word story most people don’t have the attention span to read.

Enter Farley, whom I learned about from Austin Kleon’s blog last April. Kleon, a curator of creative work, had read Brett Martin’s New York Times profile of the dude and included it on his weekly list of great stuff. That profile starts with the writer discovering a song Farley had written about him; he discovered it while Googling his own name1. I won’t spoil the story—it’s one of those long ones you have to possess the humanity and discipline to read or listen through—but, basically, Martin realizes that he’s not the only person Farley has been writing and singing about. As of today, the stay-at-home dad has a portfolio of more than 25,000 songs under a dozen monikers on Spotify name-dropping celebrities, cities and towns, and all manner of excretion. He has entire albums wishing people Happy Birthday by name (here’s mine), and has made enough money in royalties to home-school his children, make independent movies with his best friends, and afford living in Connecticut (no easy task in a state where they even charge you a yearly property tax on your car.)

Martin is conflicted about Farley: is he a goofy guy who’s found a way to make a living on music adapted for the streaming age, or a con man who’s debased himself for clicks?

Near the end, the writer muses:

“Farley represents both the best and worst of the incentives and opportunities that have taken this world’s place. Certainly, there are few creators working today in any medium who would not recognize the anxiety he embodies: that their work now lives or dies by the vagaries of opaque algorithms serving a bottomless menu of options to an increasingly distracted public. And that if they don’t bow to the demands of these new realities, their work — and by extension they — will simply disappear. Which is to say that while the experience of watching Farley work was not unpainful, as promised, neither was it totally unfamiliar.”

As a writer, I feel very deeply what Martin, Farley, and others are wrestling with today. My most recent book, which I spent more than a hundred hours on—at least 40 of which were consumed by recording the audio version, editing it, and then figuring out the easiest way to distribute it that wasn’t Audible before ultimately having to choose Audible—will make no money. My first story collection in 2023 made a few hundred bucks, offset by the cost of producing it. And I didn’t even pay my editor, Donna, who’s about the best human being alive.

But I’m also not planning to stop or change course. Even if I had the patience or the talent to make it through traditional channels, the pace of producing non-fiction with major publishers would kill me. When Chris Echols gifted me a copy of Kleon’s Show Your Work in 2021, the floodgates opened. The sea of ideas I was constantly trying to suppress in order to pretend to be a serious writer drowned out any inhibition. In 2020, I would’ve never written a rambling essay about Matt Farley. But 10 days have passed since I last scribbled anything for Substack, and I’ve felt as thirsty for the Word processor as a stranded desert wanderer for a stream of clear blue water.

Some of us simply must make things, even if they’re useless things no one understands or cares about. God is weird that way, sowing in us desires and talents without commercial merit in a world where all anyone wants is McDonald’s2.

Matt Farley has figured out a way to make music, no matter how you or I judge it, and for the music he makes to provide him with a life he actually wants, instead of sitting around complaining about the obstacles keeping him from fulfilling his life’s purpose. When he gets the time and attention, he’s even written beautiful folk songs, like the one he wrote for his alma mater, Providence College, last year. (And, of course, its 482 views on YouTube proves my, or his, point: “Butt Cheeks! Butt Cheeks! Butt Cheeks!” which he released under the moniker The Toilet Bowl Cleaners, has more than 3 million listens on Spotify).

Last month, Farley appeared on World Café, a serious platform for independent musicians that, over the years, has included live performances by The Lumineers and Red Clay Strays. He was invited on by the host Raina Douris, one of the most respected music journalists around today, who interviewed him as if he were a famous and important person, not a dude spamming the internet with songs written based on criteria, like, “what would a little kid ask Alexa to play while their parents are in the other room?”

There are a lot of quotes I love from Douris’s interview with Farley. But one in particular stuck out. It’s about growing up and finding excuses to make time to do what you love with people you love. Because it is true that it becomes harder to maintain friendships in adulthood. I am 36 and, in the time since Mickey, Jeremy, and I moved away from each other, I’ve had fewer than 10 friends who I’d call brothers: the kind who’d drop the phone in an instant and race to my house with a bag of chips and a bottle of rum when I need it most.

My former roommate, ScienceGuy84, I interact with maybe once a week, usually while wrangling our kids out the door at church on Sundays. But I miss our late-night chats about purpose, girls, and sport. That’s why, last year, I decided to spend an evening playing disc golf with him, justifying it by telling him it was for a story. The same is true of my invitation to Professor Space Rox, who spent a few days with me talking about the existence of aliens. I couldn’t care less about whether UFOs are real or not. It was all an excuse for spending time together during a season of life when work and family are all-consuming, and I can barely keep my eyes open past 9:30 p.m.

Farley told Raina:

“You get to an age where you can’t just hang out with your friends as much. We have to create this whole world of music to justify the lunch we had a few hours ago—whatever it takes to have a little guy time.”

And I feel that deeply. Perhaps it’s why I write like a man dying of thirst, hoping that one of you will read what I have to say and want to come over and play Ping-Pong or sit on the porch and smoke a pipe, find a creek to fish, or visit McKay’s and search for buried treasure together.

Before you leave, support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription for as little as $4.17/month ($50/year). You can also buy me a coffee, order a copy of my first story collection, or listen to my stories on YouTube and Spotify.

If you’re curious, here’s the song.

Here, I am referring to a bit by the comedian Jim Gaffigan on the hypocritical relationship we have with the fast-food chain. You can fast-forward to 5:50 if you want the specific reference to how McDonald’s is more than just, literally, McDonald’s. (Or enjoy the whole thing.)