Your Life Story in Under 1000 Words

From a presentation I recently gave on how to write college essays.

Earlier this week, I was at Centro Hispano speaking to a dozen high school students about narrative storytelling, which is just a fancy way of saying, “picking the story you tell about yourself.” They’ll be applying for college soon. It will be one of the many times they’re asked to write personal statements or cover letters about who they are, what they’ve done, and where they’re going.

There is a boring way to do that (usually the linear way). I write based on themes. I write for feeling. So instead of boring them with a lecture, I told them a story.

Here it is:

This photo was taken 30 years ago. It still sits in my childhood bedroom, in the house my parents have lived in since they left Argentina for the United States in the 1980s.

That’s me, and that’s my dad, Oscar. He’s a plumber. I’m a writer. On the surface, we couldn’t be more different. He was born in the countryside. I was born in a concrete jungle in New Jersey. He came to this country looking for an opportunity, and I had it at my fingertips, he told me. If I ever forgot, he reminded me in the car as we went back and forth to plumbing jobs on Saturday mornings: “Don’t break your back every day like I do,” he said. “Go to college. Do better. You’re an American—you have no excuse.”

The writer E. Alex Jung has said that if children are an extension of their parents' lives, then immigrant children are the promise of a dream deferred. That’s certainly been the case for me.

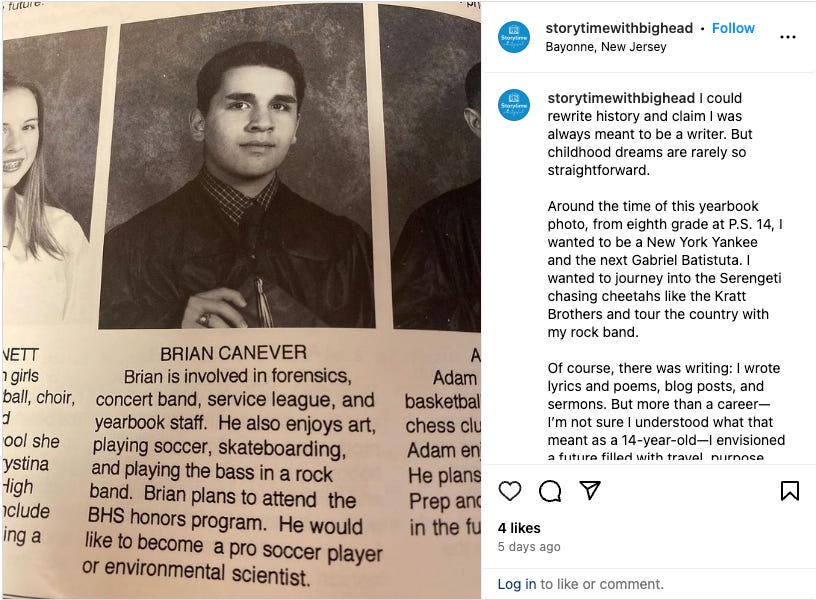

I was the first one in my family born in this country, in a town just across the water from New York City. It was the perfect place to dream. My first was of winning the World Cup for Argentina. In my eighth-grade yearbook, I wrote that I wanted to be a professional soccer player or environmental scientist. I had backup dreams too: becoming a New York Yankee, a bassist in a famous rock band. But as you can see today, none of those came true.

The little I saw of my dad as a boy was when we were on that soccer field at 16th Street Park, a five-minute walk from my house. He grabbed me after work on weekdays, and we’d go down there together. Before I was old enough to learn how to do it myself, he’d dribble a soccer ball, bounce it on his foot, then kick it high up in the air for me to chase. As I got older, he trained me how to hit a ball right, with the outside of my foot; how to place it in the furthest corner of the net, away from an Englishman’s outstretched hands.

By high school, I went to the park alone, playing with my friends: immigrant kids and their fathers from Mexico, Egypt, Poland, and the world over. For the older guys, those hours kicking the ball around together were the only escape they had after long hours at hard jobs just like my dad’s.

It didn’t take long to realize I wasn’t going pro. I was chubby—I could eat an entire box of Little Debbies and down a 2-liter of Coke in one sitting—and slow. So I had to figure out another way of keeping the promise I made my dad to not let his American dream die.

My mom bought me Nat Geo kid’s magazines. I watched nature shows on PBS with the Kratt brothers, who traveled the world teaching kids about animals and ecosystems. I could move to the Serengeti and study zoology. But high school science killed that dream quick.

Deep down, I think what I really loved about the magazines and shows were the stories. And here’s where I got lucky. My junior year, I got into the dual history–English honors course with Mrs. Prez and Sweeney, grumpy old-timers too close to retirement to follow the tightwad rules of public ed. That year, we read more than 20 great American novels, plays, and short story collections. We went on field trips to Off-Broadway plays in the city. Soon, I was daydreaming about living in the 1920s, like Ernest Hemingway and F Scott Fitzgerald. I still spend most days living inside my head.

When I got to college, my dad told me that because I had gotten a full scholarship and stayed close to home so I could help him on plumbing jobs during the weekend, I could major in whatever I wanted: business, engineering, law. I chose Latin American and Latino studies.

Majoring in Latin America helped me deepen my understanding of the culture and master the language we spoke at home. But it didn’t help me get a job. Against my parents’ wishes, I moved to Knoxville, eager to write my own story, chase my own American dream.

I got a job as a bill collector, played music at churches and coffeeshops, and wrote for sports blogs, where the bar was low and the pay was nothing. By 2013, I decided to pursue storytelling full-time. I got a master’s degree from UT and have since been published in lots of places and gotten comments from friends and strangers all over the world about the stories I’ve told. I even wrote one about my dad—about this picture—called “My Dad and the Soccer Ball,” which I gifted to him for Father’s Day and he hangs framed inside the room where he changes into his work clothes every morning.

I believe there’s a story that goes through our lives like a string. Near the very beginning of mine was this photo. That string eventually led me to a girl on my soccer team. We married in 2018 and still argue about who nutmegged the other first. The string then led to my daughter, Alba, who is almost 4 years old and has more Messi jerseys in her closet than I do. My son Gabriel Enzo, is named after the greatest Argentinian center-forward in history—my hero, Gabriel Batistuta—and Uruguay’s most iconic playmaker. Three months ago, I had my third baby, Elio Andrés, named after you know who.

I don’t know where the string will eventually lead. Maybe it will take me back to the dusty basements where my dad still works at 64. But instead of soldering pipe and priming the PVC he puts into suburban homes, I’ll have a notebook in hand. My Dad’s sacrifice has allowed me to enjoy the privileges I do today. Being here with you. Telling about how even the seemingly insignificant pieces of who you are, the parts of you from childhood you may have forgotten about, like the pictures on the shelves in your bedroom, may one day have an impact you never expected.

It’s early in the morning, the kids are asleep, and I have more to write, so I am not going to lead you through my lecture.

But I’ll say that if you get the chance to tell your story, a good place to start your brainstorming is by jotting down lists of all your key characteristics, achievements, life events, passions, struggles, and themes. Literally, grab a piece of paper and write them in columns. Then go down each list and circle the ones that connect to each other (or that you’d naturally be able to talk about without getting tripped up). Pick an overarching theme. Then go.

As you can see, there are pieces of other stories I’ve told—many of which are published on Substack and that I later adapted for my first book1—that bleed into this original story I specifically wrote for Hispanic high school juniors and seniors interested in college.

I challenge you to try to write a version of your story in 1000 words or fewer. If you do, send it to me. I’d love to hear it.

Before you go, you can support my work by buying me a coffee or ordering my first book of stories, Big Head on the Block. You can also listen to me tell stories on YouTube and Spotify.

For those of you who speak Spanish, one writer who is an expert at speaking in stories is Hernán Casciari. He recently did a 90-minute interview on Spanish TV in which he responded to every question with a story he’d written on his blog, published in books, or shared in TED Talks or on the radio. Only obsessive consumers of his work (like me) would’ve noticed. It’s a great reminder of why we should memorize and practice the favorite stories we tell from our lives; we never know when we can spit them out instead of rambling.