What Color is the Grass in Alaska?

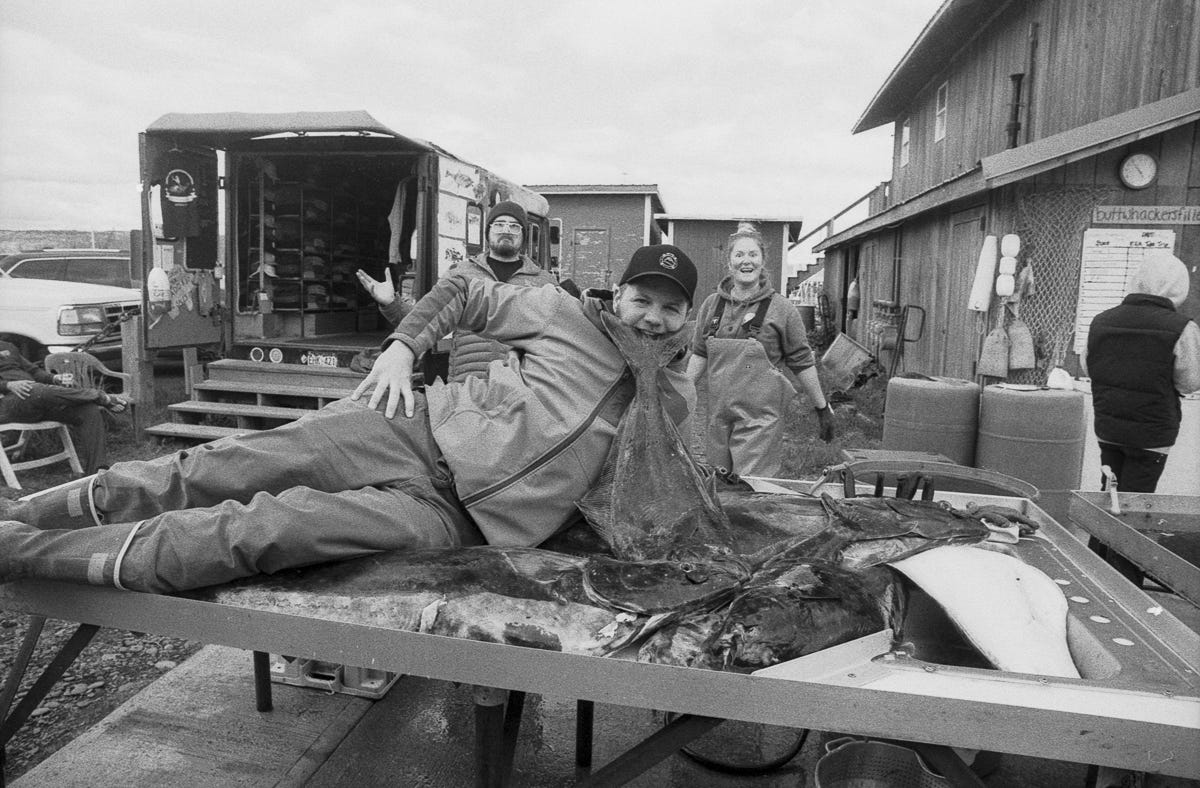

Talking with my friend Clay Duda about trading in journalism, driving 4,500 miles to the end of America, and becoming a charter boat fisherman in his thirties.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Storytime with Big Head to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.