Fàilte gu Alba

Three weeks in Scotland with my childhood best friends and what happens to us and our relationships as time passes.

Mu tha thu airson a bhith buan, na teid eadar an té ruadh agus a’ chreag (Translation: If you want to live a long life, don’t die.)

—Scottish Gaelic proverb

Note: This story was updated to its book version in October 2023.

More than 14 years have passed since the first, and so far the last, great adventure of my life.

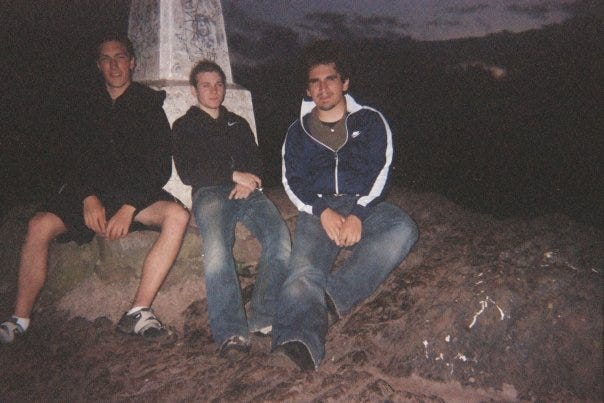

My childhood best friends and I had just finished our freshman year of college: Mickey at Rutgers, Jeremy at Calvin College in western Michigan, and me at William Paterson University, an hour’s drive north of Bayonne. Days after returning home, we boarded a plane bound for London’s Heathrow Airport on our way to Scotland, where for three weeks we explored small fishing villages and countryside hamlets, pitched our tent in the backyards of friendly strangers, and spoke late into the night about what would become of our lives once we got back home.

That year was the longest we had been apart since fourth grade. The three of us had shown up at PS 14, the magnet school for prodigies, poets, and politically connected kids from throughout Bayonne, knowing only one or two other students. Mickey and Jeremy found each other first, bonding over their shared pleasure in chucking pine cones at older kids in the park beside the school building. We became a trio a year later when Mrs. K assigned us to work on a group project we had to present weeks later in front of the entire class.

I remember the details vaguely. I think the project had something to do with creating and promoting a business or product. In our first meeting, we barely dug below the surface before uncovering what would bond us for life: we were weirdos. The proof was in the pudding. When it came time to present what we had come up with to the class, we transformed into The Boys by the Bay, whipping out fake microphones and a novelty turd and belting out a song-and-dance number about beans. The song included the line, “It sounded it like a fart, but it came out like a dart, Mr. Bean!” On the climactic note, Mickey dropped the toy turd he had been hiding to the ground, and we bowed. Our classmates looked on in a strange mix of horror and delight.

But our friendship was rooted in more than just eccentricity. We also shared an inextinguishable curiosity about the world around us. Teachers had told us there were pearls in oysters waiting to be pried open by our fingers. We only had to leave the borders of our scraggly blue-collar city to search for them. And so in 2008, at the age of 19, we booked a flight, bought two weeks’ worth of train passes, and upon landing in London took a Megabus north into a country that we knew about only because we’d watched the movie Braveheart.

Halfway through the trip, our longing for something more landed us on the Isle of Skye. As the most responsible and meticulous member of the group, Jeremy was responsible for creating the trip’s itinerary before leaving Calvin for the semester. Late one night, he had emailed to ask if we had any requests for a hike that would serve as the culmination of our foreign adventure. Mickey and I suggested “something beautiful” in a place where we could hear locals conversing in their native tongue. We didn’t realize that, to Jeremy, that translated into a 22-mile hike along a ridgeline on Skye’s northernmost peninsula, a death sentence for three city boys who had never hiked any longer than four miles in a day before.

We passed the Quiraing, a dazzling landscape of valleys, gorges, and mountain peaks, just two miles into our walk. From there, the trail disappeared along with any other human presence on the ridgeline. For the next eight miles, we struggled to carry our heavy backpacks up and down peaks as 40-mile-an-hour winds pelted our sunburned bodies. Past rolling green hills, breathtaking views of high-elevation lochs, and the ocean beyond were only endless flocks of sheep, which scampered away as we neared them. They must’ve been just as perplexed about what in the world we were doing in the middle of nowhere.

Inside our tent, eating cold lentils from Ziploc bags as the sun set over Scotland, Mickey and I were furious and exhausted. First we cursed Jeremy for stranding us on a trailless hike 3,000 miles from home. Then we cursed him for not checking the camping stove before we left to make sure it still worked. “You care more about conquering nature,” Mickey said, sticking a finger in Jeremy’s chest, “than enjoying it.” And Jeremy responded, “Maybe overcoming it is the means to fully take pleasure in it.” I didn’t bother to chime in. My focus was entirely on what lay ahead: Hartaval, the second-highest peak on the Trotternish. Pissed or not, we had a decision to make.

I’ve been reminiscing about that three-week trip for nearly two decades, plunging myself into memories I will never recreate with people who no longer live just minutes away. Mickey, Jeremy, and I have experienced so much since 2008. But the memories of Scotland are as fresh today as they were when we made them.

For much of the trip, we relied on the generosity of strangers. In town after town, we knocked on doors and asked if we could pitch our tent in their backyards. Our first night in the country, we stayed at a hostel in Edinburgh. The next morning, we took the train to Lanark in search of the ruins of St Kentigern’s Church, where William Wallace was rumored to be married. Unable to find a place to rest our heads, Mickey walked into an Oxfam store to ask if there was a hill nearby we could set up camp. He came out with a hand-drawn map from Mrs. McKinley, an older woman who lived five miles away in Ravenstruther with her eldest son, David. She said we could sleep in her garden if we managed to find the house. After we did, she invited a couple of friends over to meet the Americans who had wandered into her life. We stayed up watching the United States men’s soccer team lose 2–nil to the English while eating “sausagey-burgers” and drinking Budweisers David had picked up in honor of our visit.

Stops in Glasgow, Falkirk, and Fort William followed. Two nights before crossing over to Skye we arrived in Mallaig. On our way into town, we had walked by the Fisherman’s Mission. But instead of ringing the doorbell, we got a table at a nice restaurant a block away and ordered fish and chips. No friendly stranger invited us in that night, so we set up our tent on a nearby hill. The conversation ran out around 8 p.m., but the sun was still high overhead. Aggravated by the swarms of highland midges that had snuck their way inside and pricked our skin through our clothes, we wandered back to the mission, where we were invited in for dinner. Before eating, the resident fishermen sang “In Christ Alone, “Before the Throne of God Above,” and other old hymns from a printout sheet. Their faces were ruddied, their beards unkempt, and they swayed in clothes that smelled of fish guts, singing:

No guilt in life, no fear in death— This is the pow’r of Christ in me; From life’s first cry to final breath, Jesus commands my destiny.

The next morning we took the ferry to Skye and were bused into Portree, the island’s largest town. A kind couple let us keep the extra supplies from our packs—which weighed just under the airline’s 50-pound limit—in their garden shed while we hiked. From their home, we traveled by bus to Flodigarry, where we listened to schoolchildren bantering in Gaelic (hearing Scotland’s native language spoken aloud and James McFadden’s goal against the French in Paris during Euro 2008 qualifiers were secondary motivations for our trip). We used the facilities at the hostel to cook the lentils we later ate cold after Jeremy’s camping stove failed. And we chatted late into the night about Scottish politics, romance, and American culture with Bryan, the graying hostel worker who drove us to the trailhead the following day.

I can’t speak for my friends, but I’ve always felt like a package delivered to the wrong address. I felt that way at college in North Jersey. I haven’t shaken the feeling decades later in Knoxville. So before the fall semester of 2008, I told other students at William Paterson that my dad had been a footballer in Argentina who moved to Britain to play for Hearts, and that we relocated to the States after he retired because it was better than the alternative of being economically unstable in their homeland. I put on my best Edinburgh English accent to recount the story each time. I doubt now that any of my classmates believed it. But keeping up the fiction distracted me from the melancholy of settling back into my routine. Every day, I longed to go back. At night when I shut my eyelids, I was transported to Skye. I’d wake up in a sweaty daze and look for the next flight from JFK, despite knowing that I’d never board it.

Looking back in time appeals to nostalgics because it allows us to see the various starting points from which we could have taken roads to other places. We imagine alternate routes or stopovers along the way. But there’s a tragic element to setting our sights on the past. Mickey and Jeremy knew me better than anyone. When Ben Rector released the song “Old Friends” in 2018, they were the first people I thought of. Through our time at PS 14 and in high school, we lived within a dozen blocks of each other. We would walk or bike to each other’s houses at least once a week. We played music and soccer together and spent Friday nights in Mickey’s attic ordering pizza and drinking Snapple as we fantasized about girls and faraway lands. We planned our entire lives out, never imagining the others wouldn’t be along for the ride. Then, one by one, we left. And we’ve not returned for longer than to see our parents.

After college, Mickey moved to Miami, then Haiti, and now the Dominican Republic. Jeremy returned from Michigan and has lived within a 45-minute drive of Bayonne since. I left for Knoxville, thinking my time in the South would be a two-year diversion at best. I fantasized about future moves to Argentina, Cambodia, DC, Atlanta, and Denver that never materialized. Odds are my life will end here, a city where my children were born and my wife’s roots are deeper in the soil than my family’s in this country.

When we’re young, there’s a voice inside our heads whispering that things won’t always be the same. Friends will come and go. We’ll grow up and move away from each other. The voice tells us that we should vacuum-seal the moments we’re together and store them somewhere safe. Because the sand will only deepen at the bottom of the hourglass. And by our 30s, we’ll live in different zip codes, have families of our own, new hobbies, and careers we could have never imagined in the days when we sipped iced tea in our parents’ kitchens and bought plane tickets to a foreign land because we liked a Mel Gibson movie from the ’90s.

The morning after camping on Skye, we woke up in no mood to tackle Hartaval. Unrelenting winds coming through the valley had blasted our tent throughout the night. Our heads were pounding and our bodies sore enough that getting through the remaining dozen miles to the Old Man of Storr, the trail’s natural stopping point, without killing each other seemed unlikely. So we scrambled down a dried-up waterfall near our campsite and walked through miles of spongy flat land until we could almost see the road back to Portree.

The only barrier keeping us from hitchhiking back to warm food and beds was a forest thick with pine trees. Somewhere in those pines, the digital camera Mickey had brought to document the trip fell out of the unzipped pocket of his Sweden track jacket. In that camera were hundreds of irreplaceable photos—of Mrs. McKinley, Old Edinburgh, New Lanark, the monsterless lochs of Inverness, and Jeremy’s Polish friends who met us in Glasgow and drove us in their rented van through the green Highlands, where we occasionally stopped to listen to a lone bagpiper playing “Scotland the Brave.” After realizing it, Mickey’s body gave out, and he cried out hopelessly into the floor of loose pine needles.

Eventually, he settled his nerves and we made it to the road, where I kissed the gravel, and a van driver from Staffin drove us to a hostel. But we grieved the loss, knowing we could never put those photos into albums that we’d flip through with our grandchildren—that I could never say to my daughter, “Here we are in the land I named you after.”

We photograph so much nowadays. If we had traveled to Scotland in 2023, we would’ve each had a smartphone in our pockets ready to capture images we could post to social media for loved ones and strangers to like and comment on. But in 2008, smartphones weren’t ubiquitous yet, and the only place you could regularly access WiFi was at the library—where we went to send emails to our parents and girlfriends to let them know we were OK. The images that would’ve populated our Facebook feeds were lost among the trees.

Fortunately, I’ve held on to some. They hang safely in frames on display in the cavernous hallways of my mind palace, where I venture on gloomy days to remember who we were then. Among the images, I see Mickey’s smile from when his hair was long and tied back in a ponytail and he wore black hoodies over soccer jerseys and jeans ripped at the hem. I see Jeremy in his favorite heather gray T-shirt as we drove on his 18th birthday to watch 300 at Frank Theatres, which today sits abandoned, a relic of our youth. Later that day, we gathered to eat cake and share stories of our friendship with those outside our inner circle. Mickey and I had filmed a video for the occasion, a throwback to Mrs. K’s class. In it, we wore a pile of plastic shopping bags on our heads to imitate Jeremy’s golden afro from that time. There was no song-and-dance number. But we did mimic him memorizing a phone book, creating a solar system, and getting lost in the kind of pencil-wielding, air-drumming euphoria that drew the ire of our teachers.

Most of the time when I picture us, though, we’re back on Skye, huddled inside our tent. The resentment from the brutal hike is gone, and we laugh as we try to imagine what the future will look like once we return home. As our eyelids grow heavy with sleep, we lay our heads down for the night. The trail is not yet finished, the journey not quite over. And once we board the plane back to America, nothing will ever be the same.

Before you leave, support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription, buying me a coffee, or ordering a copy of my first story collection, Big Head on the Block. You can also listen to my stories on YouTube and Spotify.