Good morning, readers. This story was originally published on my friend Sam Scott’s Substack. If you love anecdotal, campfire storytelling, visit with him. I will be back next week with fresh work. One last thing, if you haven’t yet, buy a $5 copy of Paddlehands: The Most Epic and Absurd Ping-Pong Story Ever Told, or write me for the files or MP3s to avoid dealing with Amazon. See you soon.

I know I really don’t belong here /

Though I sometimes feel at home.— Brent Cobb, “Country Bound”

It didn’t happen after driving over the Mason-Dixon Line. Or at a gas station in West Virginia, where I accidentally filled my cup with what I thought was Iced Tea but turned out to be its more syrupy cousin.

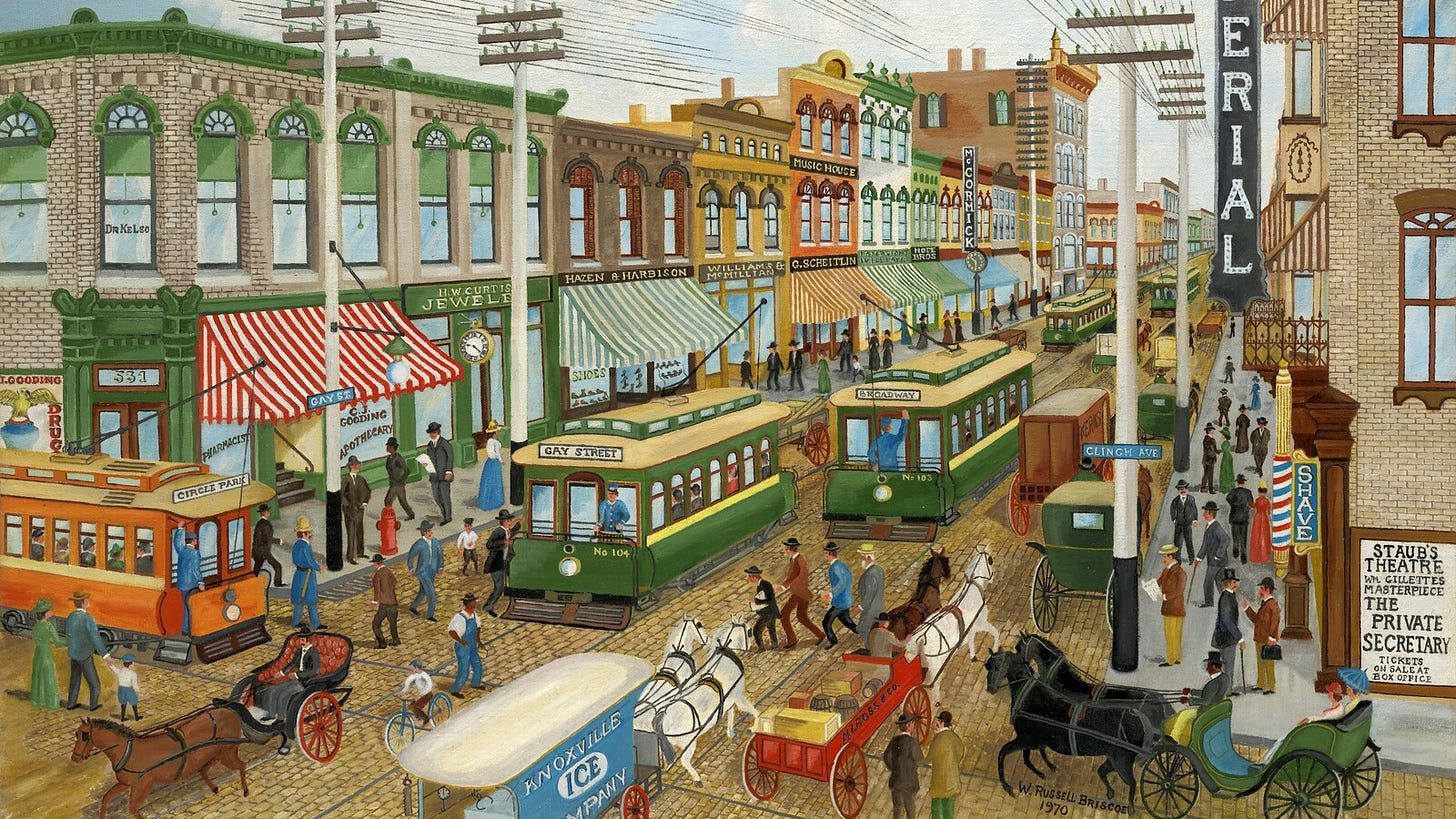

No, the moment that I realized I had crossed the border into a new country came when I pulled into a Wendy’s Drive-Thru on Chapman Highway in Knoxville for the first time.

“Whatwasatnowhun?” the lady asked, a little too sweetly, through the speaker as I attempted to order my regular: a double stack, junior bacon cheeseburger, and large fries. I fumbled before repeating myself, slowly, as if neither of us were native English speakers.

“Alright, baby, I got ya,” she said. “Ayndtodrankwithat?”

I’ve dealt with foreign accents my whole life. A few years before I was born, my parents left Argentina for Bayonne, New Jersey, a place that is technically the U.S., but where all your neighbors are from somewhere else. The Irish and Italians are a breeze to understand; they’ve been here forever. By my senior year at BHS, I could even speak enough Tagalog and Arabic to flirt with pretty women in the hallways. But I’d never needed an interpreter to speak with a fellow American before.

I’d come to the South by chance or fate, depending on which side of the faith spectrum you fall on.

When I was 17, my parents decided we should take a summer vacation south of Cape May for once. So, we drove to the Outer Banks, where I was surprised to find there were people (though most of them were tourists from other blue states). Before then, my knowledge of the South was minuscule. In history class, we’d learned about the Civil War; how some folks with strange flags down there were still angry about having to free their slaves. Ms. Hughes, a Spanish teacher who’d gone north from Kentucky, told us not everyone below the U.S. capital was a turd. She wore overalls and rode a tractor to school on harvest days. A friend, Bobby Mullen, claimed to have a cousin in the panhandle who went deer hunting before homeroom and kept his gun in his pick-up truck. But these stories seemed like fiction to me, a guy who hadn’t been within 30 miles of a Cracker Barrel before.

And then, like so many 20-somethings, my senior year of college arrived with the sudden, pressing urge to leave home. I dreamed of the mountains of Colorado and the sunny beaches of California, but the only connection I could make to anyone outside the Northeast was to a few middle-aged pastors from a city in the Bible Belt whose name I kept mispronouncing.

“So you guys are from Nashville?” I asked the men I met outside a coffee shop on a Friday afternoon that spring. They were from First Baptist Concord, a megachurch on the west side of Knoxville. They’d brought a group of teenagers to Hoboken, where I was going to church at the time, for what they called a mission trip, which confused me, as I thought you only took those overseas to places filled with pagans. My pastor, who knew I was considering seminary and a life of missionary work, introduced me.

“No, brother, we’re from somewhere even better,” they said, pulling up pictures of Neyland Stadium and the Smoky Mountains, whatever they could find that I might recognize.

“Dolly Parton owns a Six Flags there?” I asked, confused.

After I admitted that I didn’t watch college football or listen to country music, they put away their phones and suggested I make the 12-hour drive to see the city for myself. “You’re gonna be singing Rocky Top in no time, brother!”

The next night, over beer and buffalo wings, I told Nick, a friend from Pittsburgh, that I wasn’t so sure about traveling below the Mason-Dixon. But he reassured me. His wife had gone to Bible College on the outskirts of Knoxville, and he could vouch that, besides being a beautiful place with nice people who would welcome me with warm casseroles and take me fishing, I could get a job making $12/hour and still afford an apartment. (He was right; my first rental, a 2-bedroom off East Red Bud Road, cost $425/month, which I paid for by collecting on trailer notes for Jim Clayton.)

I was sold on the casseroles and the fact that I wouldn’t have to live with my parents anymore. So, in July 2011, I packed the ’98 GMC Jimmy with everything I owned—basically, two suitcases and a Taylor guitar. As “Born to Run” played in the background, I drove down I-81 with a two-year plan. That’s the time, I figured, it would take for me to acclimate to life outside the urban jungle, get involved in the Knoxville church-planting scene, then apply for a scholarship to study foreign missions at Reformed Theological Seminary in Charlotte or Orlando before flying off to Argentina, Cambodia, or Tajikistan.

Knoxville was meant to be the first stop on a world tour.

But I struggled. I met great people in and out of church, found places to play pick-up soccer and eat real Mexican food (i.e., the kind featuring intestines and cow tongue). Even the accents grew easier to understand. But, as the days turned to months, the courtesy I’d received seemed suspect. People greeted me with waves instead of middle fingers, asked me all kinds of questions about my life, but they never invited me over for beer and fellowship. Religion was a weather system down here, and yet, I couldn’t square the smiling folks in their Sunday best with the words and phrases on their bumper stickers or the lack of love in their surface-level friendships. I couldn’t understand the obsession with Boomsday, the Gadsden flag, or the SEC.

And yet, after two years, I renewed my lease to stay.

Instead of seminary, I got a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Tennessee and the opportunity, during the World Cup summer of 2014, to relocate for three months to Bristol, Connecticut, where I interned at ESPN headquarters, certain I’d be back in civilization before Christmas. I looked for new apartments, joined a church. But instead of placing me back in familiar territory, God shot me right back down to purgatory, until 2017, when I met a girl on a soccer field whose family has been in East Tennessee longer than mine has been in the New World. Within a year, we were married. And just as my stipulation was that she learn to love Lionel Messi and eat foreign food once a year on my birthday, hers was to saddle up and buy more orange because she had no plans to ever leave God’s country.

A decade after figuring out how to make it through a drive-thru order without stuttering, the thickness of my Jersey accent has faded. Though I still meet people who ask me where I’m from. Some—the ones I worried about when Nick and I had that conversation in a Hoboken bar—ask where I’m from from. Since the pandemic, I’ve watched more transplants make it to the Scruffy City and experience the same wonder I had upon seeing the Sunsphere for the first time. And, by the grace of God, I’ve found as many Bible belters who are kind to strangers because they think it’ll get them into heaven as those who do it because their parents taught them it’s the right thing to do when there are pilgrims in their midst.

Today, even when I fail to understand this place or am infuriated by something said or done, Knoxville is synonymous with home.

For the first half of my life, I lived in the shadow of the Big Apple, where all God’s people gathered and the cold, gray winters reflected humanity’s desperate need for salvation. For the last 14, I’ve lived in the shadow of the Appalachian Mountains, where I shoot guns at Coke cans in my friend’s backyards and the winters aren’t as harsh, though the soul of man is just as much in need of saving. Because even though there’s a church on every corner, there is still a chasm between behavior and belief. And some days, I really would prefer being told to go to hell than have my heart blessed by a Baptist.

I still can’t believe sometimes that home is a city I didn’t know existed when I asked the Lord to send me far from Bayonne to a land of strange languages and cultures. And yet, my family sings every word of Rocky Top when the Vols are on the court, and I haven’t tasted jelly sweeter than the one my wife’s Mamaw cans on a ridge in Grainger County, where the roads are windy and the tomatoes grow like manna from heaven.

So, for now, find me at the Cracker Barrel, ordering my biscuits with a glass of tea like any homegrown bubba. Stop by if you have a minute. Only God knows where the road will take us. Though I reckon it won’t be far from here.

Before you leave, support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription for as little as $4.17/month ($50/year). You can also buy me a coffee, order a copy of either my first story collection or my epic Ping-Pong novella, or listen to my stories on YouTube and Spotify.