Not So Different After All

It's easy to think we're fundamentally different from our families. Listen to their stories, and you may find out you aren't that different at all.

Listen to this story for free.

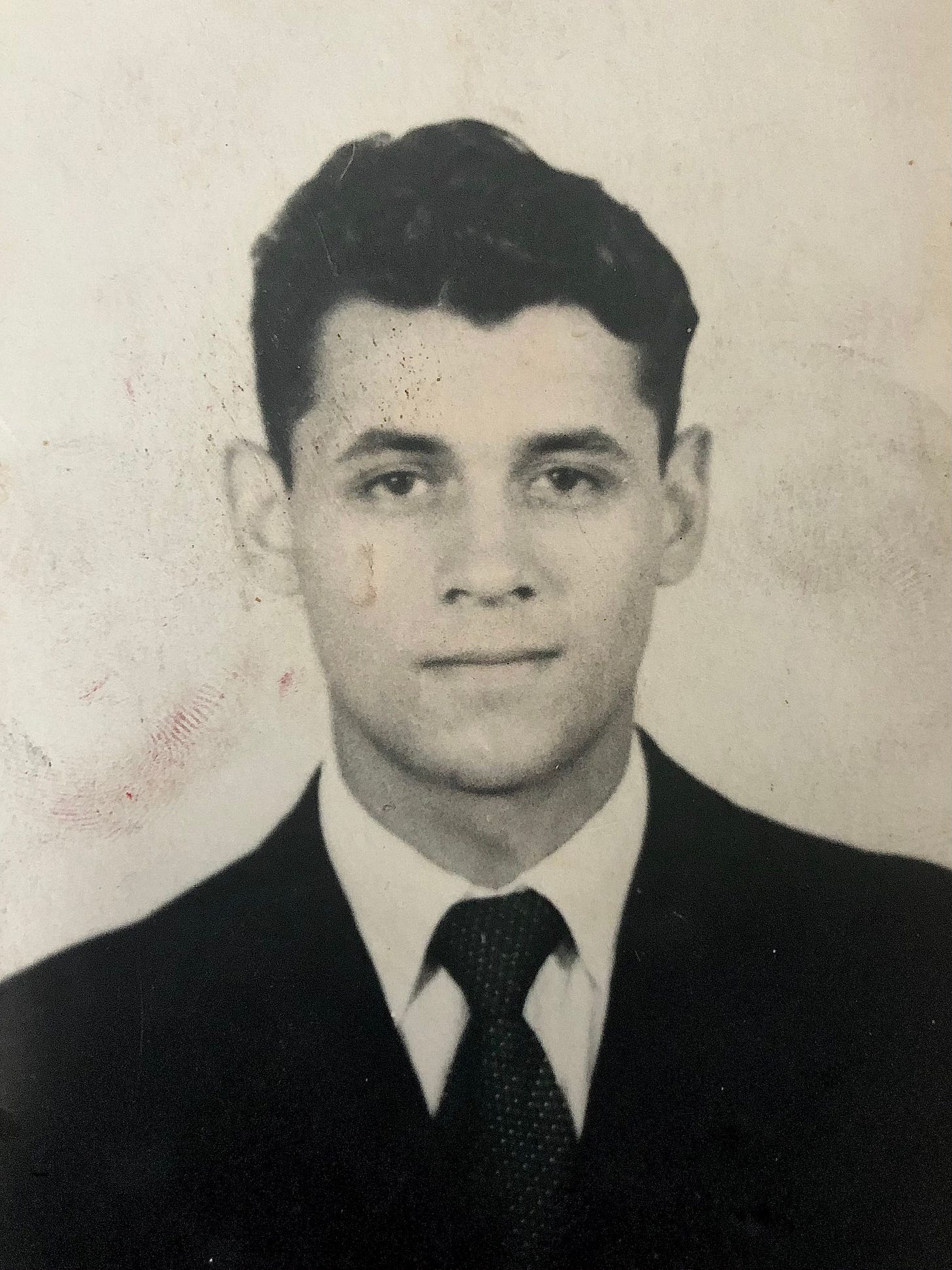

For as long as I've been alive, my maternal grandparents have lived in the apartment just below my parents. Until I left Bayonne at 22, Nono and Nona were everpresent. My car keys hung in their kitchen, and I rarely got out the door without Nono asking where I was going. If I got in late after hanging with Mickey or Jeremy, I usually came in through their apartment and crashed in their spare bedroom so I wouldn’t wake my dad, who was up by four getting ready for work.

Like any traditional immigrant woman, Nona kept me well-fed on a diet of Argentinian empanadas and tortillas españolas. But my favorite of her culinary specialties were her canelones, pasta tubes stuffed with meat and spinach that she’d make in the wintertime to keep my belly warm. On weekends when she didn’t make canelones or empanadas, she’d bake french fries in the oven and set a big bowl of them down on the kitchen table, where Nono and I watched thousands of hours of muted soccer together. “We don’t need to listen to those nitwits tell us what was going on,” he’d say about the commentators while cursing at Pep Guardiola or whichever coach was unlucky enough to be managing the team he didn’t like at the time. Though I knew the real reason he liked to keep the sound off was so that it wouldn’t interfere with his monologues about world politics or how he’d beat Barcelona or Man City 7-0 in the Champions League Final if he could just travel back in time and grab a dozen street kids from his old neighborhood in Rosario.

In 2018, I’d been gone for seven years and was growing increasingly worried about how much longer I’d have my grandparents with me. They were just entering their 80s, and the sand that had once filled the top bulb of the hourglass of their lives was trickling quicker than ever down the neck to the other side. So I decided to record them for the first time, turning on the Voice Memo app on my phone and letting it run for hours as we spoke.

While they told me about their lives before I knew them, I jotted down notes of what until then had been half-remembered memories. Nona told me about her upbringing in a neighborhood of Italian immigrants near the Central Cordoba soccer stadium. “You know it,” she said. “You’ve seen the house before.” Nono grew up a few miles west in a small place on the outskirts of el Parque Independencia. They met by chance as teenagers walking home after the state fair. Nono and his best friend approached Nona and hers; he used a corny pick-up line about her bowlegged gait, and the couples paired off until they got to the bus stop. Even though Nona said his friend was much nicer to her, she got stuck with Nono, the funny one. They married, had my mom, and in the 1970s moved abroad to Australia, then the U.S., then back to Argentina, and eight months later returned for good to Bayonne, where they’ve lived with my parents, in the same house on 19th street, ever since.

My favorite thing about Nono has always been his storytelling. Much like soccer and empanadas, the after-dinner conversation—la sobremesa—is an inextricable part of Argentinian culture, and my brother and I listened intently as Nono recounted stories from his youth in Rosario. How he jumped fences at soccer stadiums and outraced mounted police. How in the summers, on land his relatives farmed, he took siestas under eucalyptus trees, hoping to see the apparitions of dancing gauchos—Argentinian cowboys with big hats and extravagant knives they wield to fend off cattle thieves and prepare barbecues. But all he ever saw was the occasional scrap between giant native ducks.

Like many of history’s great storytellers, Nono is a shapeshifter: in one story, he’s a champion street fighter viciously beating down a local boxer with elbows for claiming in the gym that he could take any boy in town; in another, he’s an idealistic union leader doing battle against the political class for the good of his fellow man.

One detail of his biography is undeniable: Nono had little formal schooling—he put away the books after sixth grade and went to work to help pay the bills after his old man walked out on the family. But despite not getting his diploma, he has always adored education. In one of his famous stories, his teacher tells the class how Christopher Columbus and other European explorers, whose names the kids knew from the city’s street signs, had discovered America when Nono shot up a hand. “Señorita, pero Colón no era explorador como usted dice,” he said. “Era un pirata.” Because only pirates take gold and silver, regardless of whether it’s for themselves or for the crown. She ordered him face the corner and not say another word, then had to turn her back to keep from laughing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Storytime with Big Head to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.