'Ni de Aquí, Ni de Allá'

On home, plus a translation of Hernán Casciari's viral story "Lionel's Suitcase."

El árbol que tú olvidaste siempre se acuerda de ti /!Y le pregunta a la noche si serás o no feliz / El arroyo me ha contado que el árbol suele decir / Quien se aleja junta queja en vez de quedarse aquí.—Atahualpa Yupanqui, “El Árbol Que Tú Olvidaste”

Note: This story was updated to its book version in October 2023.

A story about Lionel Messi went viral in Argentina the week after the 2022 World Cup final. Its author, Hernán Casciari, read a condensed version, which he titled “Lionel’s Suitcase,” on a national radio program in the days between the final and Christmas. The story is about Messi’s journey from being a 13-year-old boy who left Argentina for Spain after his family could no longer afford the medical treatment he needed to grow normally to the man who captained his nation to its first World Cup trophy in 36 years.

A video of Casciari reading the story appeared on YouTube. Soon after, Messi—who was back home in Rosario for the holidays—sent a voice message to the radio station telling them that his wife, Antonella, had shown him a clip on Instagram, and they cried together while listening to it. Like Messi, I cried when I heard Casciari read the story for the first time. In fact, Casciari—who had immigrated like the Messis and thousands of other Argentinians to Barcelona just before the country’s economic collapse in 2001—cried while narrating it.

During his time in Europe, Messi became an ambassador for Argentinians abroad. Even though Spain had attempted to persuade him to switch allegiance and play for their national team when he was still a teenager, he resisted acclimating to his new country. He sought to be Argentinian, despite the criticisms of his compatriots for not being Argentinian enough, especially after their loss to Germany in the 2014 World Cup final. In the media outlets of Buenos Aires, they called for him never to return home. But that was impossible. Because Messi, like so many immigrants, had kept his suitcase packed and his eye on the front door from the moment he landed in Spain.

Immigration has been at the forefront of my life, even before I moved away from home in 2011. Bayonne, the city in New Jersey where I grew up, is a place of resettled departures. You’re as likely to hear Spanish, Polish, or Arabic on the street as English. My own home was divided: upstairs, where I lived with my parents and brother, we mainly spoke our second tongue; downstairs, my maternal grandparents spoke only Spanish. So I had no choice but to be fluent if I wanted to have a relationship with them.

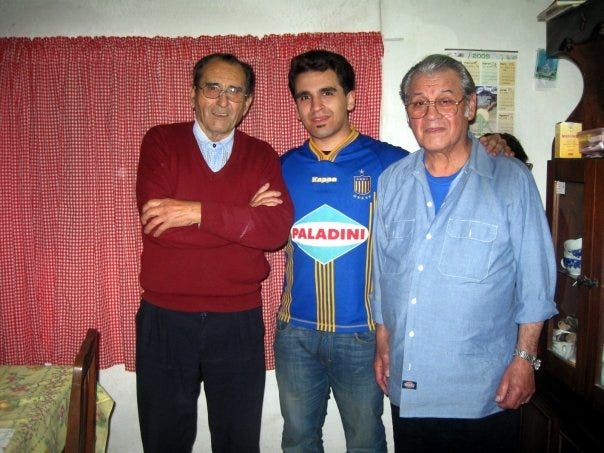

I’ve always been curious why people, including my family, come to America just to create time capsules of the places they left behind. If 1970s Argentina had been cryogenically frozen and thawed into a house on 19th Street in Bayonne decades later, that was my home. We drank mate cocido, a tea brewed with yerba mate leaves from South America, and cooked extravagant asados, or barbecues, on the traditional Argentine grill my dad had built in the backyard. We spoke with the hard shh sound people from the River Plate basin make when pronouncing the double l (as in ella or silla), and listened to zambas from folk singers like Atahualpa Yupanqui and Jorge Cafrune. When I was five, my father dressed me in a Boca Juniors kit he’d bought on a trip back home and took pictures for the family. Later I chose to support Rosario Central, a less famous club from my grandfather’s city that I fell in love with because of his stories of watching them in good times and bad throughout the 1950s and ’60s. A sticker with their blue-and-yellow crest is on the water bottle I drink from as I write this.

Even though I had access through my family to a world that was five thousand miles away, I wished we had gone to Argentina more often. Every summer, the Spanish kids flew to Galicia while I languished in Bayonne. It was a time before Skype, YouTube, or WhatsApp. My only connections to Argentina were skirt steaks and chorizos, Gabriel Batistuta, and the sportscaster Andrés Cantor (he of the half-minute ¡Gooooooooooool! calls).

By January, weeks after the 2022 World Cup final, I’d listened to “Lionel’s Suitcase” a dozen times. I was listening again with my headphones on while I unpacked boxes in the basement of the house we had bought in north Knoxville, where I watched Gonzalo Montiel score the winning penalty to give Argentina its victory against France. In one of the boxes, I found a copy of a story I had written for a Spanish literature class my junior year at William Paterson University. In college, I majored in Latin American and Latino studies because I longed to connect with my parents, my grandparents, and the people they left behind in a land I felt a part of despite having spent so little time in. For that lit class, Professor Rodriguez assigned us to write one original short story entirely in Spanish. I wrote mine about Nono, my maternal grandfather, who baptized me Cabezón, harassed me at soccer games until high school, and taught me how to tell a story.

Nono fascinated and confounded me. For years before I left, he captivated me with stories of soccer and his childhood in Rosario, the same city where Messi was born. He’d narrate them for me like he was giving a lecture broadcast to millions over the radio, even though it was just us at the kitchen table, drinking wine and eating Lay’s chips and cold cuts. But as much as he let me know him through his lectures, he was still an enigma. He would fall asleep muttering to himself with repetitions of Yankees baseball games or cowboy Westerns on mute in the background. And when he’d speak about the Argentina of his past, he’d do it with an affection he didn’t feel for the U.S., a country he had become a citizen of despite speaking only enough English to greet the mail carrier. He was unsettled and disillusioned, and I thought I knew why: he needed to go back home while there was still time.

Nono dismissed the idea, saying it was too late to go back. The parents and grandparents of my Dominican and Mexican friends had built wealth in America so they could return to their towns and villages with luxuries that had escaped them as children. Nono had come to this country, accumulated few luxuries, and decided this would be the place where he’d die. Whenever I prodded him about returning to Rosario, he would quote a line from the Argentine folk singer Facundo Cabral: No soy ni de aquí ni de allá—I’m from everywhere. I’m from nowhere.

I titled the story I wrote for Professor Rodriguez’s class El Hombre Viejo (“The Old Man”). It opens with the same lines that open this story. They were written by the folk legend Atahualpa Yupanqui, whom Nono would often listen to while lying on the couch in his living room with his eyes closed. The lines translate to “The tree you’ve forgotten always remembers you. And it asks the night whether or not you’re happy. The river tells me that the tree often says, ‘Whoever leaves collects grief instead of staying here.’”

I wrote most of “The Old Man” while lying on the same floral couch where Nono listened to that song. The story opens with him sitting there, reflecting on the lines as they ring out from the cassette player nearby, and follows him through an average day in his life: arguing with my grandmother, going outside to water the plants, and talking with me at the kitchen table as a soccer game plays on the TV in the background. Inner dialogue runs throughout the story, with Nono asking himself if he should have stayed in Rosario and questioning whether the exchange of countries was worth it as he nears his final days. Inside of him, a tug of war is taking place between his monotonous life in New Jersey and the one he still had time for in the home he’d never forgotten.

Most of the story takes place in a dream after Nono fell asleep listening to Yupanqui. I shout him awake, reminding him that he promised that very day we’d buy airplane tickets to Argentina so I could watch Rosario Central play. (We took this trip together in 2009, a year after I wrote the story.) I printed out “The Old Man,” clipped the sheets together, and gave the manuscript to Nono as a Father’s Day present. I’m not sure how the story wound up back in my possession. Maybe he returned it to me with instructions on where to make changes to the grammar and vocabulary or rewrite the action. Or maybe I printed out a second copy and hid it away so I could find it and remember those years when I still believed, naively, that going back in time was possible.

I wish I could peel back the layers of my own identity—being American, Northern, from New Jersey, and of Bayonne, and at the same time, Latino, South American, Argentinian, and Rosarian. The layers stack on top of one another, sometimes sliding into place like puzzle pieces and other times more like colors splattered on a blank canvas. Being told by my parents that I’m American because I was born here and by strangers in Tennessee that I’m not because of the places my family tree traces back to. It’s a bizarre experience growing up in Hudson County, where everyone seemed to be from somewhere else, then moving to Knoxville, where peoples’ roots stretch back to the Mayflower. I often joke that I moved to the TV version of America, with its blue-eyed blonde girls, sweeping suburbs, and country music, only once I’d left New Jersey, eager to write my own story, as my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents had written theirs before me.

My connection to Bayonne, where I lived for 22 years, will likely sever when my parents leave or die. I may only go back to show my children, telling them as we drive through the sea of red lights, “Appreciate how good you have it, because you could have been born here, where the breeze smells of sewage, the sirens blare past midnight, and a parking spot close to your house is as hard to find as a stranger who smiles back inside Shop Rite.” But that city is tattooed onto me, together with all the other markings that make me who I am.

When I went back to New Jersey that first November after I’d left for Knoxville, friends told me I spoke with the hint of a Southern accent. I recoiled. I fought (I fight) so hard to say youse instead of y’all, pie instead of pizza, to care when the New York Giants make a playoff run (and to remind people that they play in New Jersey). Like Messi in Casciari’s story, I fight to preserve my accent, just as I’ve fought to refine a very specific kind of Spanish despite being raised around all other kinds of Spanish speakers, so the Hondurans and Colombians I play soccer with at the park will pause and ask, “Are you Argentinian?” and Argentinians will ask, “Are you Rosarino?”

I envy the people who stay—who are from and of the same place. And yet I know how many people wish they had other origins to return to. I remember the disappointment on Haley’s face when she got her 23&Me results and they read 99.1 percent white. “Just like everyone else in East Tennessee,” she said—a British girl with enough French mixed in to turn her skin bronze in the summertime.

I want to ask every person I meet in a church pew or at the playground with my children about where they came from, where they’ve been, and what their struggle has looked like. On the one hand, I’m curious. But I also know personally how complicated identity can be. I wonder how other immigrants and transplants maintain their customs. Do they drink yerba mate from a calabash gourd in the afternoon or settle for a cup of black coffee? Are their offices covered in flags and pictures of places they escape to when they’re feeling blue? Do they lie back on the couch, like Nono, soaking in the sounds of home? Or are they like Lionel Messi, with his suitcase right beside the door, always ready to take the next flight back to Rosario?

Lionel’s Suitcase

The following is my translation of the condensed version of Hernán Casciari’s “Lionel’s Suitcase,” which is available in Spanish on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts. A longer version of the story was published in Orsai magazine in February 2023.

Saturday mornings in 2003, TV3 in Catalonia would broadcast games from FC Barcelona’s youth teams. And in the conversations between Argentinians who had left and resettled in Spain, there were two questions that were repeated endlessly: How do you make dulce de leche by boiling cans of condensed milk—that was the first question because we were desperate—and at what time did the 15-year-old from Rosario who scored goals in every game play? Those were the two most important questions.

During the 2003–04 season, Lionel Messi played 37 games across four youth and senior teams for Barcelona. He scored 35 goals. I remember the TV ratings for the Saturday mornings when he played were better than the prime-time numbers. There was already talk about this kid, the Future No. 10. In the barbershops, bars, and the stands of Camp Nou, people spoke about who he was and where he’d come from. The only one who didn’t speak was him. In the postgame interviews, he’d respond to every question with a simple sí or no. Sometimes he’d thank the interviewer. And then he’d look down at his feet.

The displaced Argentines, the immigrants, would have preferred a loudmouth. That was more familiar to us than a quiet boy. But there was something gratifying for us when, finally, Messi would piece together a sentence. Because he’d swallow all the s‘s. He’d say fúl instead of falta and gambeta instead of regate. And we felt relieved, for we had discovered that kid was one of us. He was one of the immigrants who had never put away their suitcase.

I should explain this. At that time in Barcelona, there were two types of immigrants. There were the ones who, after their airplane had touched down in Barajas or Prat, tucked their suitcases away in a closet, far in the corner, forgetting about Argentina. And they started to say vale, tío, hostia immediately. Then there were those of us who had our suitcases just inside the door. We never put them away. We preserved our customs—for example, drinking mate, our yeísmo. All the time, we’d say shuvia (rain), cashe (street), so that we’d never forget to speak with the yé.

Time passed, for everyone. And suddenly Messi, the teenager who didn’t talk, became the undisputed No. 10 for Barcelona. With his ascension came league championships, Copas del Rey, Champions League trophies. Yet he knew, as much as we did—the other immigrants—that the hardest thing to maintain, above all else, was his accent. It wasn’t easy to keep saying gambeta instead of regate. Because when time passes, you become embedded in the society that took you in. You merge with your surroundings. Yet we also understood that this was our last stand: maintaining our way of speaking. And, incredibly, Messi was our leader in battle. The kid who didn’t speak kept alive our way of speaking.

So suddenly we weren’t just enjoying the greatest soccer player we had ever seen—because going to Camp Nou in those days was unbelievable. But we were on guard, making sure some Spanish slang hadn’t found its way into his vernacular. That it didn’t show up in an interview. We celebrated when he kept speaking the same way. And beyond his goals, we celebrated that in the dressing room, he always had his thermos and his mate.

Out of nowhere, Messi became Barcelona’s most famous person. But just like us, he never stopped being an Argentinian in some other place. The Argentinian flag he carried to celebrate every European Cup fascinated us, as did his stance when he traveled to represent Argentina in Beijing in 2008 to win Olympic gold for Argentina without the club’s permission. His Christmas holidays were spent in Rosario despite having to play a tournament in Camp Nou in early January. Everything he did was like a subliminal message to us, those who in 2000 had arrived with him in Barcelona. It is very hard to explain how much it meant for those of us who lived so far away from home: How he had carried us up from the apathy of the dreary world we lived in. How he, a kid who didn’t speak, helped us to never forget our place in the world. To hold tight to our compasses. Messi made us happy in a way that was so peaceful and pure that when the insults began to arrive from Argentina we couldn’t make sense of them.

Spineless. They said You only care about money. They told him Stay in Europe, mercenary. You don’t feel the shirt. You’re Spanish, not Argentinian. If you quit once, think about quitting again. You’re not one of us.

For 15 years, I lived far away from my country, and I swear that I never endured a nightmare like hearing voices of disdain from the place I love most in the world. There is no pain more unbearable than hearing from your son or daughter the words Messi heard from his son Thiago when he was six years old: Daddy, why do they hate you in Argentina?

My voice is breaking. I can’t catch my breath. I have two daughters—one is Argentinian, the other Catalan—and if either one of them were to say something like that to me, I’d burn with resentment. I don’t know how I’d go on living. That’s why Messi’s decision in 2016 to retire from the national team was almost a relief for us, the immigrants. We couldn’t bear to watch him suffer any more because we knew how much he loved Argentina. We knew, from the time he was 15, the incredible effort he made to continue being Argentinian. To not sever the umbilical cord. When he retired in 2016, it was as if suddenly Messi had decided to remove his hands from the fire. But not just his—ours also. Because the criticisms from those assholes back home burned us too.

And it’s at that moment of the story that the most unusual and extraordinary thing in modern football happened. The evening of June 26, 2016, when Messi decided he was done with the insults and abandoned the national team, a 15-year-old boy wrote him a letter on Facebook. And it ended with this line: Consider staying, Lionel. But stay so that you can enjoy yourself—which is what these people want to take from you.

Seven years later, the boy who wrote that card—Enzo Fernández—was the standout young player of the World Cup won by Lionel Messi. Because Messi returned almost immediately to the national team. And he announced that he did it so that all the children who wrote him letters and shared messages on social media knew that giving up is not an option in life. Upon returning, he won everything there was left to win for his country. Everything that he dreamed of winning. And he silenced the voices of his critics.

Not all of them, of course. Because some, including during this very World Cup, found him, for the first time ever, to be vulgar. It was after the Holland match when he said, Que mirá, bobo. Andá payá, bobo. (Essentially, Messi was saying, “What are you looking at, dimwit? Go stand in the corner.”) For those of us, the immigrants who had monitored his accent for more than 15 years, that sentence was perfect. Because he swallowed all his s‘s. Because his accent was intact. It soothed us to confirm that he was still the same kid who helped preserve our joy when we were an ocean away from home.

Now some of us have returned. Some remain in Spain. But all of us have savored watching Messi return to Argentina with the World Cup trophy in the suitcase he had never stowed away. Because that suitcase has remained by his door from the day he stepped foot in Europe.

This epic story would have never occurred if the 15-year-old Messi had tucked his luggage in his closet and succumbed to the pressure of saying vale, tío, hostia. But he never confused his accent. He never forgot his place in the world. For that reason, all of humanity desired with such passion to see Messi finally win this. Because never, in the long list of humanity’s greatest heroes, had we seen a man like him standing atop the summit of the world. A simple boy. One like any of us. This December, as in every year before, Messi left Qatar, as he had left Spain and France, to spend Christmas with his family in Rosario. Like always. To wave to his neighbors. To play with his children. His habits are unchanged. His customs remain the same. The only thing that is different is what he brought in his suitcase.

Before you leave, support my work by buying me a coffee or ordering a copy of my first story collection, Big Head on the Block. You can also listen to my stories on YouTube and Spotify.