Yesterday was Easter Sunday, and I’m assuming that many of you celebrated by wearing pastel-colored clothing, hiding plastic eggs for your children, and then eating all their best candy while they weren’t looking. If you’re a Vols fan, it’s likely you spent at least the afternoon crying or looking up the last time a team got called for 7,500 fouls in an Elite Eight match-up. And if you’re religious or have a religious family, you may have even gone to church for the first time since Christmas.

I am religious and go to church most Sundays, though I struggle on Christian holidays to distinguish what I’m supposed to be celebrating from the commercial aspects of the festivities. For that reason, I’ve been thinking a lot about Holy Week and what it represents beyond the preacher’s sermon or an opportunity to feel guilty or happy or eat chocolate bunnies.

According to the tradition, on the last Thursday of his life, a carpenter-turned-preacher by the name of Jesus had dinner with his best friends, a small band of average dudes he’d recruited over three years to share the news that his Father had sent him to redeem the world. That night, while praying, Jesus was apprehended by armed guards and brought before the occupying Roman government, to whom he was described by local religious leaders as a dangerous traitor deserving death. He was executed on a cross the next morning. A few days later, he came back to life, hung out with his friends for a while, and then went back to heaven to be with God.

I’m not a preacher, nor am I very wise in the ways of religion. In college, the Intervarsity kids labeled me a troublemaker for associating with the Young Democratic Socialists. The socialists thought I was Pat Robertson. In any group I was a part of, I was either the least or most religious person. I still am, and I prefer it that way because it leads to great conversations.

There is one character in the Holy Week story named Barabbas who I can’t stop thinking about, in part because his name appears in many of the songs and merch by the Louisiana rapper Aha Gazelle, who I listen to when I work out at the YMCA.

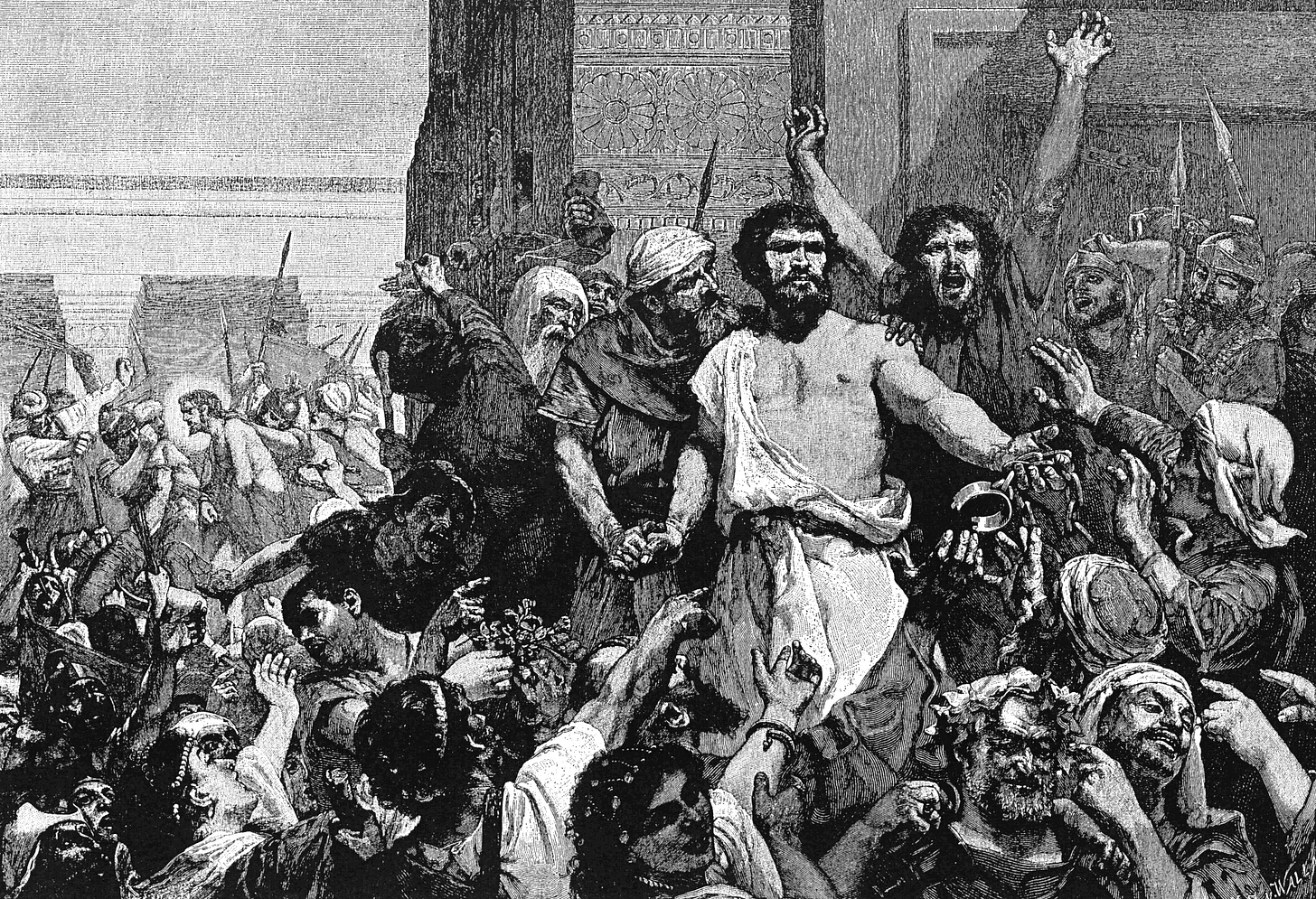

Some on Reddit have interpreted Aha’s heavy usage of the term “Free Barabbas” as a reference to the mainstream Christian belief that Jesus was sent by God to die, and that it was He who killed him, not Pilate or the priests. According to accounts from all four New Testament accounts of Jesus’s life, Barabbas was a convicted killer counting the days until his execution when he was unexpectedly pulled from his cell and presented before an angry mob in front of the Roman judicial courts. We don’t know what he looked like, only that he’d taken up arms against the Romans and was justly deserving death according to their justice system. Pontius Pilate, as a sign of goodwill, was offering the people a choice of who to free or kill.

While they were both considered threats to the status quo, Jesus stood in stark contrast to Barabbas. Sure, he was a rebel preacher who caused some upheaval by mobilizing thousands of people in the countryside whenever he spoke. But he was not (yet) a threat to Roman imperial power. The people came to Jesus for healing and miracles. Barabbas they went to for insurrection and war.

Even though I have professed faith in Jesus’s bold claims since I was 17, I empathize with those who believe he was a liar pedaling self-help mantras to the naive. Part of that is because I know how distrusting I can be. I also know that I am a coward who can get caught up in a crowd. Outside those court steps, Jesus posed a threat to many of the good things I believe about myself.

It’s easy to imagine standing there on the day of his sham trial declaring that Barabbas be freed instead. Because Barabbas offered the world a real promise. He killed for what he wanted. He’d fight until his people were free. We understand violent figures, especially Messianic figures like Paul Atreides, the protagonist of the Dune novels. It’s much harder to understand meekness, which can be written off as softness, and hope for a better day, which can be synonymous with delusion.

It’s possible that if I had been present 2,000 years ago, I would have felt compassion for Jesus as blood poured out from his wounds. But it’s just as possible that I’d have done nothing about it, like when I drive past the homeless camps on Broadway or see a crying woman in the street and walk by, hoping she doesn’t ask for help or money.

I can’t stop thinking about it, even at this point in the timeline when I’m supposed to be happy and moving on to thinking about pools opening on Memorial Day and fireworks blasting on the Fourth of July. Hearing “Free Barabbas” is like hearing myself declare a statement I know I’ll regret but can’t keep from uttering, perhaps a little bit like the Mexican fans who chant puto! at soccer games and then go home to make dinner for their spouses, tuck children into bed, and pray for God to heal their mothers’ cancer.

I hope you had a great weekend, whether it was spent cheering on the Vols, hunting Easter eggs, or taking family photos in pastel-colored clothes after Sunday service. I am excited to share more of these weekly reflections with you, and I promise they won’t always be this heavy. Next week’s will likely be about some time I recently spent smoking a pipe with my friend, who will now and forever be referred to in this publication as Apocalyptic Cowboy.

In the meantime, drop me a line in the comments or via email about what you’d like to see more of in this column or publication. See you next Monday.

Your thoughts on Barabbas are so interesting. I have a tradition of listening to Jesus Christ Superstar (the original studio recording) on Good Friday, and maybe because of the way that work positions Judas as a tragic hero I always find myself empathizing with him: clinging to a wrong-minded perspective with ferocious self-righteousness and doing irreparable harm in the process.